Luther College students and professor create a scale to measure hate

“Why do we insist on hating so much? Why aren’t we more understanding? Why aren’t we slower to anger and more easily swayed to understanding, and empathy, and compassion, and forgiveness? You can’t really address those questions if you don’t have a tool to measure those things.”

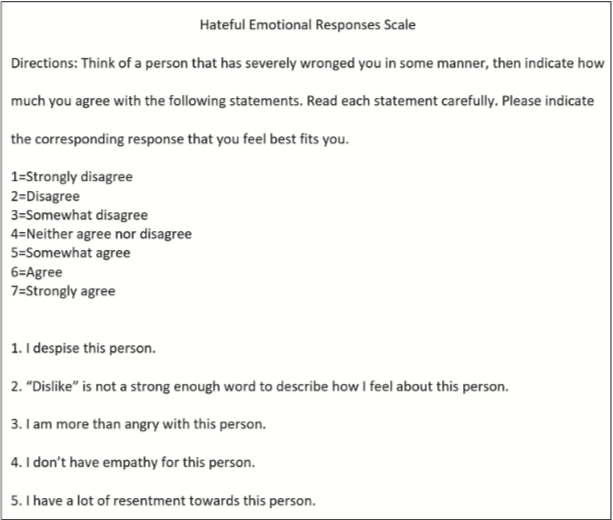

Questions such as those posed by Professor of Psychology Loren Toussaint are what prompted him and his team to create the “Hateful Emotional Responses Scale (HatERS): Development and Initial Evaluation.” Created by Toussaint, Reverend Dr. Michael Barry, Alanha Kiel (‘17), Maxwell Meier (‘18), Wyatt Anians (‘19), Michael Enmoto (‘19), and Kacy Rodamaker (‘19), the study creates a scale to measure hateful emotions toward an individual or group. The group created a survey of five questions that reflect the group’s definition of hate.

The group defines hate as “an intense, emotional response experienced by an individual following perceived wrongdoing or perceived ill-will on the part of another person or group of people.” This definition came out of a variety of sources, as basic as dictionary definitions or as complex as scholarly essays and studies.

“The first step we did was try to define hate,” Enomoto said. “You would think that would be pretty easy, [but] not a lot of people agree about what hate is specifically, to them and about others. Hate is a very general word, and it can mean a lot for things in regards to racism, sexism, hatred for self, hatred for others. There are a lot of different topics that cover hatred, and we wanted to define that first and foremost. I think that was probably the hardest part of the study, being able to define that.”

The study, which is free to access, was published in the “Journal of Hate Studies” at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, in December of 2020. However, work on this project began in 2017. The group began by discussing and examining forgiveness, thinking that hatred would be the antithesis of that. From there, they searched for a definition of hate, which proved difficult. They ended up developing their own definition on which to form their study’s questions.

Toussaint’s team had Luther students answer the long list of questions, from which they determined the most important questions, and whittled them down to five. These questions addressed components of the definition, as well as the responses someone has when they are feeling hatred.

This study differs from many others of this sort because it provides a measure for hateful responses, instead of viewing it as an emotion to be felt and not quantified. In an interview with Toussaint, he quoted the psychologist Edward Thorndike who said, “if a thing exists, it exists in some amount; and if it exists in some amount, it can be measured.” Toussaint believes that if hatred exists, it is in a calculable amount.

Hatred can manifest in various forms, including racism, xenophobia, sexism, homophobia, or a plethora of other strong negative emotions felt between groups or individuals.

As the research process for this study began shortly after the 2016 election cycle, there was a lot of hate in circulation at the time. The group thought a scale to measure hate would be applicable in the instances of hate they were seeing all around them in the media.

“The start of the research came about after the 2016 election,” Anians said. “You can imagine that at that time, tensions in our country were elevated, and they have been for the past couple of years. We have some ideas from then that would be equally as relevant today.”

The team hopes HatERS can be used to measure the hate that is ever-present in contemporary society. Enmoto shared why he thinks this study was important and relevant for finding forgiveness.

“[The scale] is really just about moving forward and not looking back all the time, which is very easy to do when we talk about hatefulness,” Enmoto said. “It is usually an instance or one specific problem that arises for some people that causes them to not be able to forgive themselves or forgive other people.”

Because the scale helps people understand the problem and causes of hatred, people can use this to understand why they hate someone or some group and work to move past it. Toussiant hopes that people will pay attention to the issue of hatred so that it does not become normalized in society.

“We talk a lot about hatred as an unfortunate outcome of ignorance, xenophobia, and all kinds of things that contribute to it,” Toussaint said. “But often we do not have the convenient and necessary tools to be able to quickly index what’s happening. As a citizen of planet earth, you can’t hardly see things that are transpiring and not wonder, ‘should we be doing something to help us better understand why hate develops so rapidly and so quickly, and what can we do to change that?’”